Becky Cooper

Villa Lena, 2025, Session 1

April 2025

Rosita, Oral History interview re: Toiano on April 25, 2025

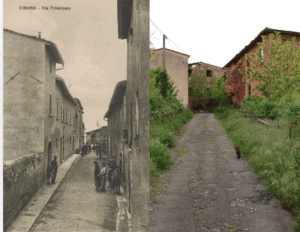

I had arrived a litle early to Toiano, the ghost town that’s about a 20-minute walk from Villa Lena and is book-ended by a small cemetery and a church on one end, and steep, sandstone cliffs on the other. The big white and grey dogs that serve as the village’s guards had been growling the whole time.

Rosita surprised me at the top of the village —the side that backed into the woods — and waved at me to join her. Those growling dogs weren’t hers after all.

I walked along the short street that makes up the entirety of the town that’s been inhabited since medieval times and has now mostly given itself back to nature. Where there had been living rooms, there was now just vegetation. A stray cat ate meekly out of a baking tray. A fig tree grew out of a broken second-story window.

Three other, smaller, auburn dogs encircled her. They’d been abandoned by their owners who had left the village, and Rosita’s been looking after them for years. “Be nice,” she scolded them, as they tried to nip at my legs.

Rosita it is said, is the last resident of Toiano. There are other owners (four besides her), but she and her husband are the last full-time residents. She had recently started coming to Villa Lena, because she is an art restorer, and had been hired to restore the frescoes in the villa and elsewhere on the property. (Despite a lifetime of living in the area, she had only been inside the villa twice at the time of our conversation.)

After our talk, I think about how similar our work is: we both stubbornly refuse the passage of time. We spend our days researching what had been there before, in order to fight decay and erasure. Our work is to resurrect the dead, and to bring forward the invisible. But we’re both also aware that time always wins.

She invited me into her house. We entered a dark hallway behind a heavy door and climbed the stairs to her living room and kitchen, with ancient exposed beams. She exited briefly to lock her dog upstairs because she could tell I’d be scared otherwise. I took the time to look around her house, which was very orderly: photos of her wedding. Her fridge, bathed in light from the open windows, was decorated with magnets of cities she had visited, as well as the Albanian flag, for her husband. She had kitschy tiles on the backsplash behind her stove of sayings in English and Italian: “Adesso o mai più / It’s now or never.” “Meglio tardi che mai / It’s better late than never.”

We sat at her kitchen table, and I sipped coffee as she patiently answered my questions, her voice low and scratchy from decades of cigare+e smoke. Her eyes were heavily lined in black, and she smiled easily. We spoke in Italian, mine halting and imperfect, and this is a translated, abridged version of our conversation.

Becky: Hi, I’m Becky. I’m a journalist and a writer, and I’m very interested in memory. Since coming to Villa Lena, I’ve become very interested in Toiano, particularly in what it is like to be the last resident of a ghost town. Thank you for taking the time to speak with me. Were you born in Toiano?

Rosita: No, I was born in Pontedera and grew up in Palaia. This house belonged to my great- grandmother. Then it was my grandmother’s and my dad’s, too, after he had separated from my mom. I’ve been here since 2000, but I was studying in Florence, then, so I’d be in Florence for three or four days and here only on the weekends. I’ve lived here full-time since 2005 — more or less since I graduated. But I would always come here as a child.

Becky: I imagine it’s changed a lot?

Rosita: Yes, unfortunately. 70% of the town is owned by someone in Como. If we five private individuals were not here you would not even come here. We cut the grass. We do the street cleaning. The municipality never comes.

Becky: Did you meet your husband in this area?

Rosita: No I met him in Palaia. He’s Albanian, but he was doing some work in Palaia. We’ve been married for ten years now. He’s a truck driver here in Tuscany for the COOP warehouses. Before that he was a bricklayer.

Becky: How long has your family been here?

Rosita: My great-grandfather was a gamekeeper. He was a guardian — like a forest ranger. My great-grandmother was a housewife. I think she was born in 1909, more or less, and my grandmother — her daughter — in ’33.

Becky: When you walk on the street of Toiano, what do you feel?

Rosita: The most beautiful thing about Toiano is definitely nature. The panorama. I’m always taking photos, photos, photos, as though I were a tourist, even though I see it every day. The landscape is always changing: from the summer to the snow it always changes. And then I also have memories — so many memories — from childhood. We came to mass here for Christmas and for Easter with my parents.

I’m not sure if you know the story, but the church bell of Toiano was stolen a very long time ago and it is in Florence. It’s called the Toianella. It now rings at the Palazzo Vecchio.

Becky: When did the church close?

Rosita: The last time I was in the church I think I was maybe 10 or 12 years old? So, 1985 or so. They closed it because people stole everything from the church. They broke the doors, stole the reliefs from the walls. And also because there’s a danger that something might collapse.

Becky: What was Toiano in general like when you were young?

Rosita: When there were more people? It was always quiet like now. But when my grandmother was young, the village was inhabited. There were lots of shops. There was a club where they danced to music. There was an oil mill and a barber.

Becky: I met tourists who told me that 50 years ago, they ate at a restaurant on August 15th at a table that stretched the entire length of the street.

Rosita: Yes, it was right next door. They did that. Becky: Every year?

Rosita: Yes.

Becky: When did the restaurant close?

Rosita: I think I was last about ten-years-old in the restaurant too, so about 30 years ago… It is a shame my grandmother isn’t here. She knew everyone. Their names, everyone who lived here, all the stories. She died a year ago.

Becky: I’m so sorry. How old was she? Rosita: 85.

She also told me stories of the second World War, which arrived here and which she lived through. The Germans threatened the people of the town. There was the war, there were shelters where people hid. There was a German base nearby. There was a wall where the Germans lined people up one day, and shot them all. Then the Americans arrived and liberated the town — the same story as everywhere else. She always told me these stories when I was little.

Becky: Did your grandmother tell you stories of how it felt in the village to see everyone disappearing?

Rosita: Well my grandmother moved, too. She went to Palaia. But my great-grandmother stayed here. Before Toiano, she lived in Renacchi.

Becky: Were they the Benvenuti in Renacchi? [I’d just finished reading Giuliano Bandecchi’s book about Toiano (Toiano: Tra Storia e Mistero, published October 2024) and in it, he includes the witness testimony of Elvira’s sister Silvana (p.126) saying that the Benvenuti in Renacchi had comforted her mother on the day of Elvira’s murder.]

Rosita: My grandfather was a Benvenuti — he married my great-grandmother’s daughter. My grandmother told me she knew Elvira. My grandmother was a little older than Elvira, but they were, let’s say, around the same age.

Becky: Does the story still weigh heavily on the village? Rosita: Yes, yes.

Becky: In what sense?

Rosita: Many people come because of the story. And at the time Elvira’s death caused a scandal. Today you see there are so many similar stories, but…

Becky: It still has power over the area.

Rosita: Yes, yes. Because it was a small town, and everyone knew each other. Becky: Do you think Toiano’s fate is linked in some sense with Elvira’s death?

Rosita; No, I think this was a tragedy that would have happened anyway, but maybe without her murder, there wouldn’t be as much interest in the place today. People look for Elvira here in the cemetery.

Becky: But she’s not here.

Rosita. Right. But people think she is. They come here with those ghost sensors. Becky: Do you ever feel lonely here?

Rosita: No. If I ever want a little chaos, then I go to Livorno, Pisa. I always travel for work, too.

Becky: You studied art conservation in Florence, yes?

Rosita: Yes, I studied art with Cassina furniture design and then I did fine arts in Florence, with a focus on decoration.

Becky: How did you decide to come back to live here?

Rosita: I like it here. It’s peaceful. I can work outside doing furniture design. And painting. [She points to the roses she’s painted on her walls, climbing over and around her window frames.] If I were to leave here, I would find another, equally lost place. I can’t stay in the centers. I work in the centers of the most beautiful cities. But that’s enough for me. I need to see the greenery.

Becky: And when people left this village, where did they move to?

Rosita: At first Pontedera, to the big factories. Yes, some to make Vespas. But then people also scattered. To Massafra. To Genoa.

The houses that are still standing now are the private ones that were passed down within families. The gentleman next door lives in Florence, but the house was his mother’s.

Now, unfortunately, everything has been put up for sale here. I was the only one who didn’t want to sell.

Becky: Why?

Rosita: In part because I like it here. It has sentimental value for me. But also because I feel somewhat obligated. If they were to come and make a resort out of this town I wouldn’t like it anymore.

Becky: Who tried to buy it from you? [Note: The Palaia tourist board insists that Toiano is not for sale.]

Rosita: There’s a company, but who’s behind it, no one knows. I know it’s an English company. If they’re successful, maybe we’ll find out later, but for now they won’t say who it is other than that there’s a company that’s interested. All I know it was put up for sale by an agency in Florence. [She shows me the listing: 5.9 million euros. It says 5,500 square meters. 100 bedrooms. 100 bathrooms. She says it had been listed at 6.5 before] But then after you pay that, you have to pay about 40 million to fix it, so we’ll see if the company has the ability to make an investment of that kind.

Becky: And they want…

Rosita: The whole countryside. All of it. Becky: To change it into something touristy?

Rosita: Yes, something like that. Everyone else wanted to sell. I was the only one who didn’t. One gentleman here is very old and his son never comes. And the guy from Como who owns 70% has wanted to sell for a long time. For years. So I was the only one. I was almost forced to.

Becky: Forced in what sense?

Rosita: Forced in the sense of if I were to stay and it were turned into a resort, I wouldn’t like that

— first of all. And then, forced in the sense of, if everyone wants to sell and I’m the only one refusing… If I don’t sell, then no one else can sell…. At least we can hope that if they renovate the village, they’d maintain the structure of the town.

Becky: And also that they’d feel the responsibility to maintain the spirit of the place.

Rosita: Yes, if it becomes too modern, it ruins the essence of the place. And of it being Tuscan in general. If they don’t maintain that, I’d be sorry.

Becky: How would you describe what makes something essentially Tuscan?

Rosita: The Tuscan spirit? The structure of the houses is rustic. If you put marble in it from Mexico, it’s no longer Tuscan. The houses usually have an exposed face. At Villa Saletta, I’m not sure if you’ve seen it, they’re renovating it, but they’ve kept a lot of the traditional exteriors.

[We hear some noises from outside. Tourists, walking down the road. She looks out her window and says hello.]

Rosita: Here in Toiano, you see everything. It attracts strange people. Look, I found this video. [She pulls it up on her phone.] I didn’t know what they were doing. It looked like a cult. They were all women with black and red on and then they walked around in a circle in the wood that I had cut for the fireplace.

I’ve seen naked people taking pictures. People dressed as zombies. As dinosaurs, everything. Becky: I’m also interested in the people who visit Toiano. They seem to be looking for something.

Rosita: I regret that in all these years I haven’t taken photos of all the visitors. I have some, but I would have liked to make a book of photographs of all of them. Of the special tourists who visit Toiano. It would be so interesting.

[She smokes a cigarette out the window.]

Becky: Do you find that living in a ghost town changes your sense of time?

Rosita: I don’t. Well, I don’t like watches in general. In fact, I don’t have any clocks in the house. I don’t like time that much. I think what it changes more is organization. There’s no aqueduct here. I have a cistern, and there’s a well down here where I get the water. But I don’t cook with that water, so I always have to get a bottle of water either from the source in Palaia or from the source in Forcoli, so that takes organization. But it’s not tiring to do, because it becomes a habit, right? You just have to bring the bottles with you to fill them up when you pass by.

Becky: But you have electricity?

Rosita: Yes, yes, but we’ve never had water. My dad went to the municipality 40 years ago for the aqueduct, and … nothing. Even with Villa Lena a few years ago, they held meetings, etc etc. But the municipality never interested my father that much. A little because they’re deaf to the concerns of Toiano and because Palaia is not a rich municipality. But if they had put in an aqueduct 40 years ago, Toiano would not be like this. Because even if a private individual had wanted to buy a house here, they’d learn there’s no aqueduct and they’d get scared and not buy it. Without water, you can’t even make cement. So if we had had an aqueduct, many people would have bought houses here — foreigners, Italians. There was a man from Marche who had wanted the house, but not without the aqueduct.

Becky: Are you happy that there is no aqueduct to avoid this?

Rosita: No, I would have been happier if Toiano had been bought by many private individuals, and it had become a small town with a bar, a restaurant. I was happier with the company. Because without it, maybe the village will close, and it all will disappear. I think this future is possible.

Becky: Do you think it’s too late now?

Rosita: Yes. It would require an investment of so many millions of euros.

They did work here six years ago to stop the hill from coming down in a landslide, which cost something like a million euros. Before those hydrogeological works, they couldn’t even issue building permits. Now, at least with the works, they can.

Becky: But isn’t Toiano protected by the FAI?

Rosita: Yes, but here money is also important. They [the ‘company’] also wanted to know who owns the church, because they would like to buy the church, and they want to know who owns the land around it, because they’d like that too.

Becky: And what’s the story of the Christmas ornaments?

Rosita: Yes, okay, that’s a bit of a load of crap, in quotes. Basically there had been a girl who had been renting here, who is from Palaia, and she had created this initiative “Portiamo una pallina a Toiano.” And then she wrote about it in Tirreno, which is a local newspaper. So for the first few years, Toiano was full of people bringing these ornaments. But if we don’t take them down, the wind carries them all around. Last year, I wrote on Facebook asking that instead of bringing an ornament, could people bring a little cat box, because there’s a cat colony here and each box costs less than the ornament they would have otherwise brought. It was a much better Christmas, because if I don’t take off the ornaments, then they stay here or the wind carries them and they break and pollute. I have already removed so many.

There have been so many initiatives for Toiano over time: town hall meetings, first with our parents, then me. Meetings with the mayor, with Villa Lena for the aqueduct. Nothing has ever been resolved.

Becky: Has the man who lives in Como and owns 70% of it here ever lived in Toiano?

Rosita: No, because first it was owned by his father, and he passed it on to his children. They never come to the meetings. They’ve renovated that beautiful house there at the top of the bridge — the one on the right. They fixed it all, and they did it right, I saw the inside. But they’ve never even stayed ten days in it. Every now and then they come to clean, but otherwise they’re never there at all.

Becky: Are you afraid of what will happen to the village after you?

Rosita: I would be sorry if it closes, or if I can’t come anymore, even as a visitor. But would I be willing to pay a thousand euros a night to come back to sleep? No, no, that’s for sure.

Becky: Do you have a favorite place in the village?

Rosita: The bridge. I spend many hours there, even at night. It’s meditative. Becky: What do you like about the bridge?

Rosita: The 360-degree view. It’s true that here in the area there are many beautiful panoramas, but you don’t get it like this where it’s all around. Even if you go to Volterra, you can see one side but not the other.

Becky: And I heard that the bridge used to be a drawbridge?

Rosita: Yes, long before the war. If you look at the broken medieval wall on the right, you can see where it connected.

Becky: Are you ever afraid of Toiano?

Rosita: No. I walk through the woods even at night here. Becky: What is it like at night?

Rosita: Peaceful. I know a lot of people are scared, but I think it’s more dangerous to live in a big city. What’s there to be scared of here? You might come across an animal. You might be unlucky enough to find a bad guy — but you can find that anywhere. And ghosts, which everyone asks me about, I’ve never seen.

Becky: Do you believe in ghosts?

Rosita: I believe in something greater than ourselves, but, honestly, if I saw a ghost I’d be happy. Because that’d mean tomorrow we’d be here, too.

[When we finish talking, she walks me out of her house, back through the dark hallway, where my eyes haven’t adjusted so I can’t see anything. She escorts me to the foot of the village, pointing out where the barber had been, and the dance club, and she helps keep the dogs away. “Even I don’t like the white one,” she says. “It’s strange.” She lets me snap a picture of her, and the small dogs look on at their queen, who is tethered here by nostalgia, beauty, and obligation. In the photo, Rosita smiles broadly, her hands at her waist, and she wears a black sweatshirt on a warm spring day, that says: Fly away.”]